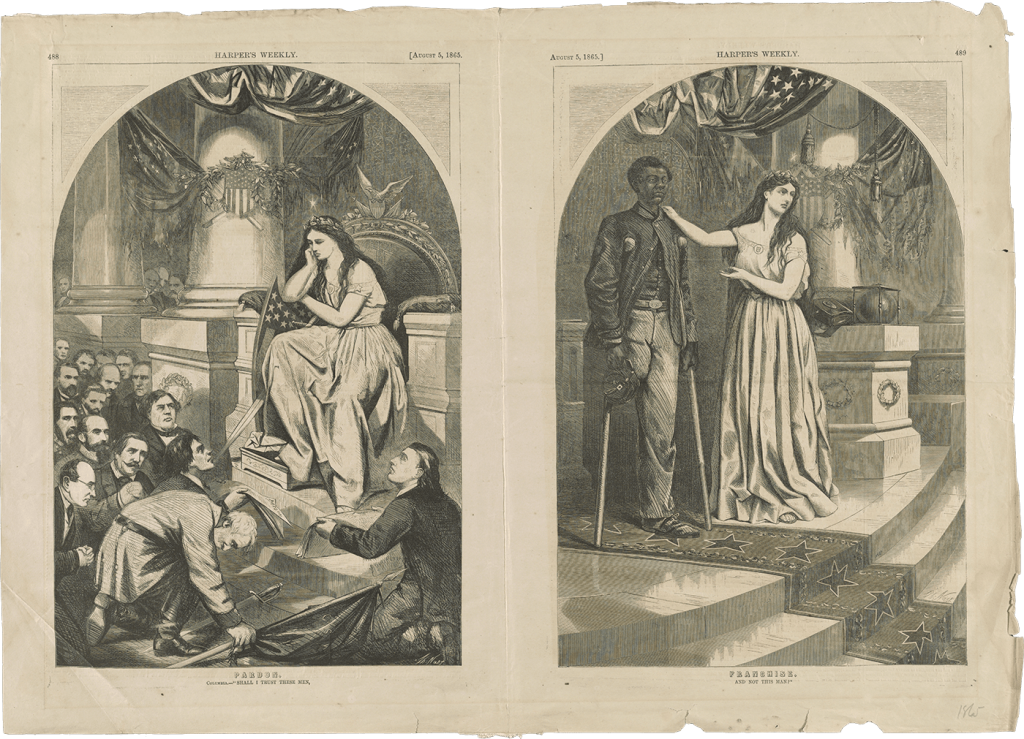

The 15th Amendment banned racial discrimination in voting. In 1869, Congress debated several drafts—some of which provided more extensive protections. Even as each house passed broader proposals, Congress settled on language that only focused on voter discrimination based on race. The 15th Amendment was passed by Congress on February 26, 1869, and ratified by the states on February 3, 1870.

Special thanks to Kurt Lash from the University of Richmond School of Law for sharing his research and expertise. Kurt Lash, The Reconstruction Amendments: Essential Documents (University of Chicago Press, 2019).

Turn device horizontally for easier scrolling.

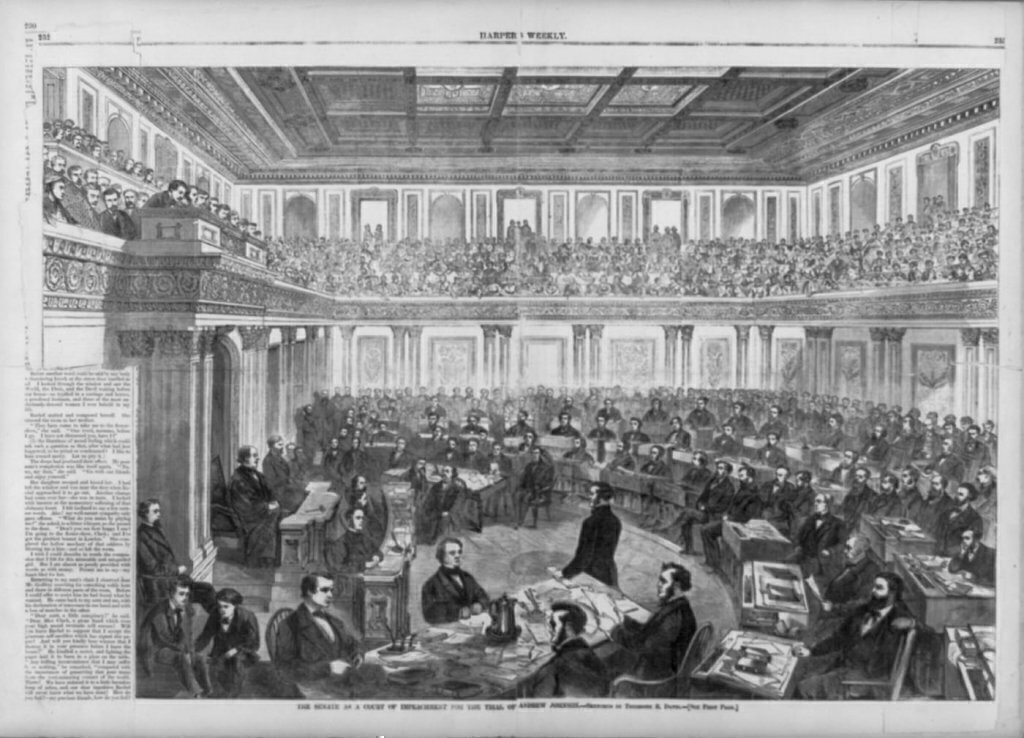

Event — March 2, 1867

Event — July 9, 1868

Event — January 11, 1869

Draft — January 11, 1869

Draft — January 23, 1869

Draft — January 27, 1869

Draft — January 28, 1869

Draft — February 8, 1869

Draft — February 20, 1869

Event — February 23, 1869

Draft — February 25, 1869

Draft — February 26, 1869

Event — February 26, 1869

Event — March 4, 1869

Event — April 9, 1869

Event — May 12, 1869

Event — February 3, 1870

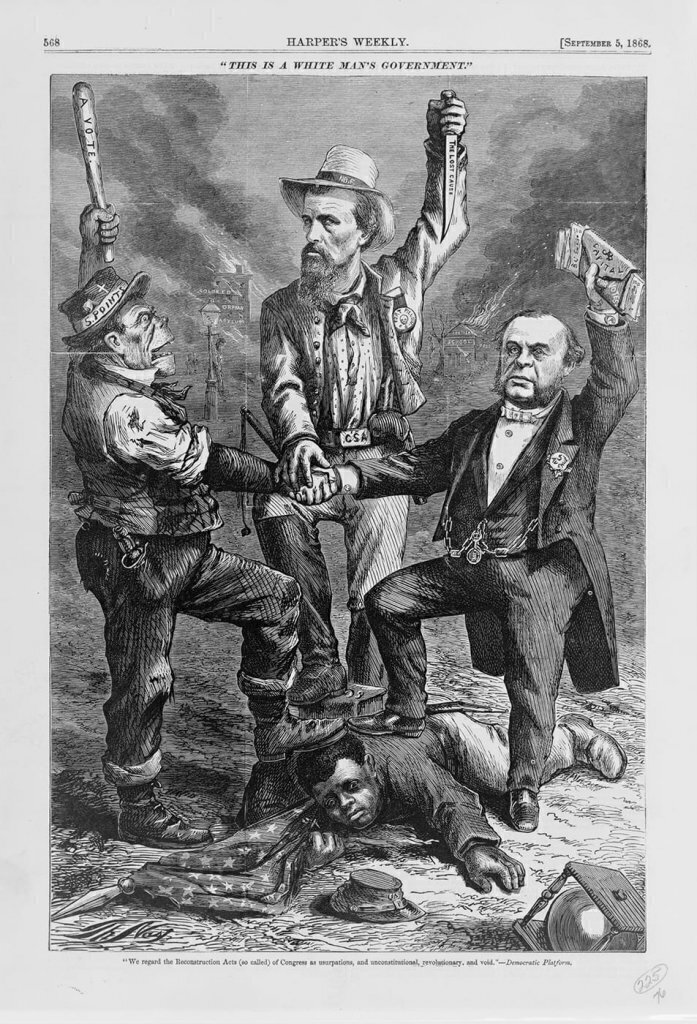

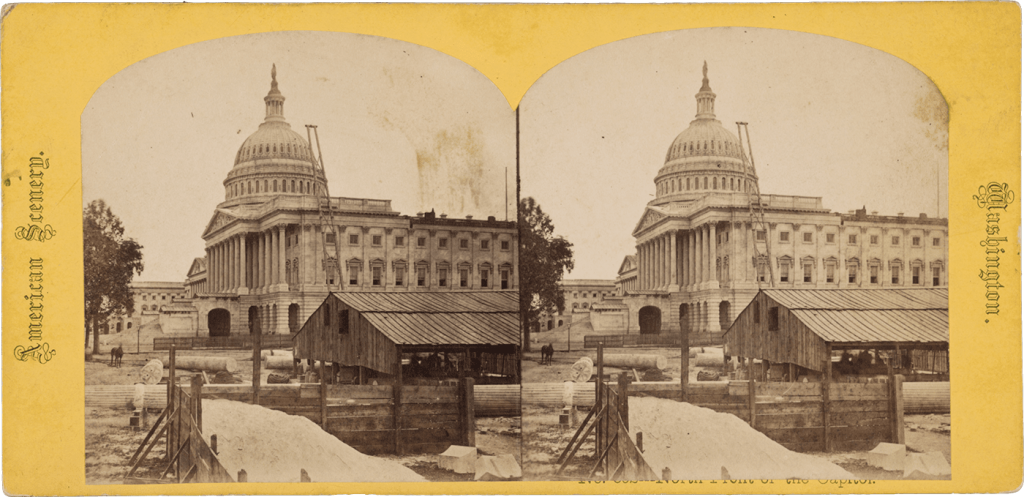

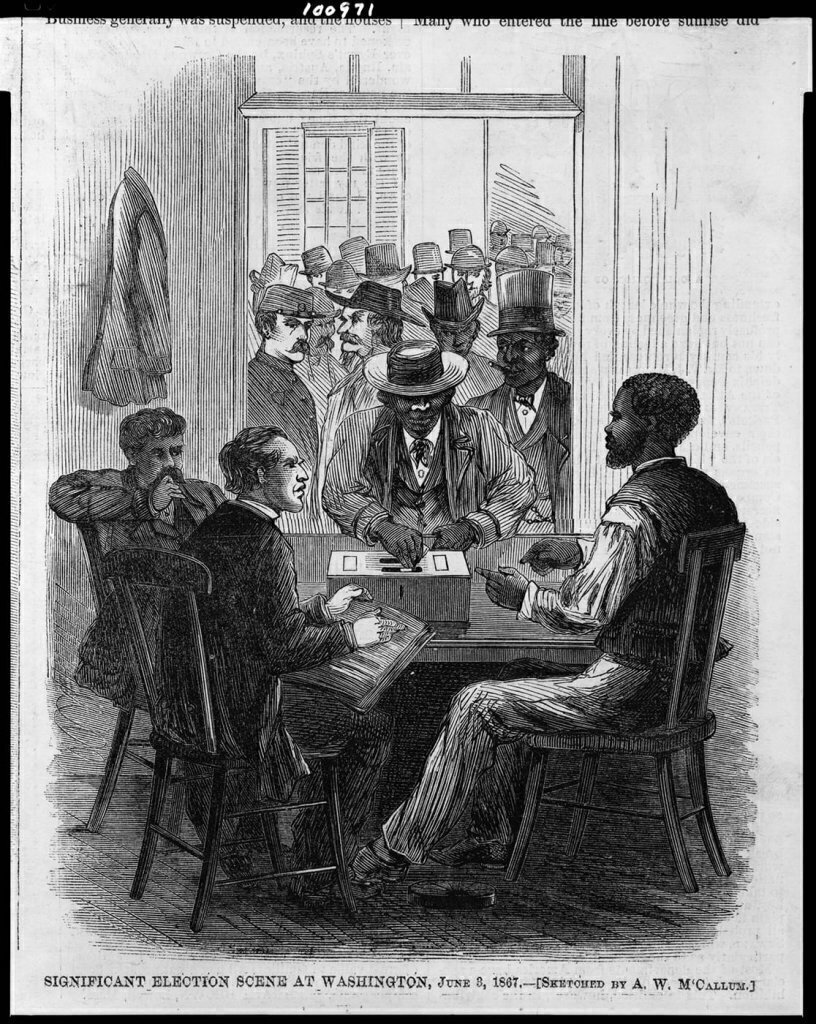

The Reconstruction Acts required the former rebel states to allow African-American men to vote on equal terms as white men and therefore participate in the creation of new state governments and constitutions.

The 14th Amendment addressed citizenship, freedom, and equality. Section Two pressured states to grant males equal access to the ballot box without regard to race by promising reduced representation in Congress if they did not. However, the 14th Amendment did not expressly prohibit states from denying African Americans the right to vote.

January 11, 1869

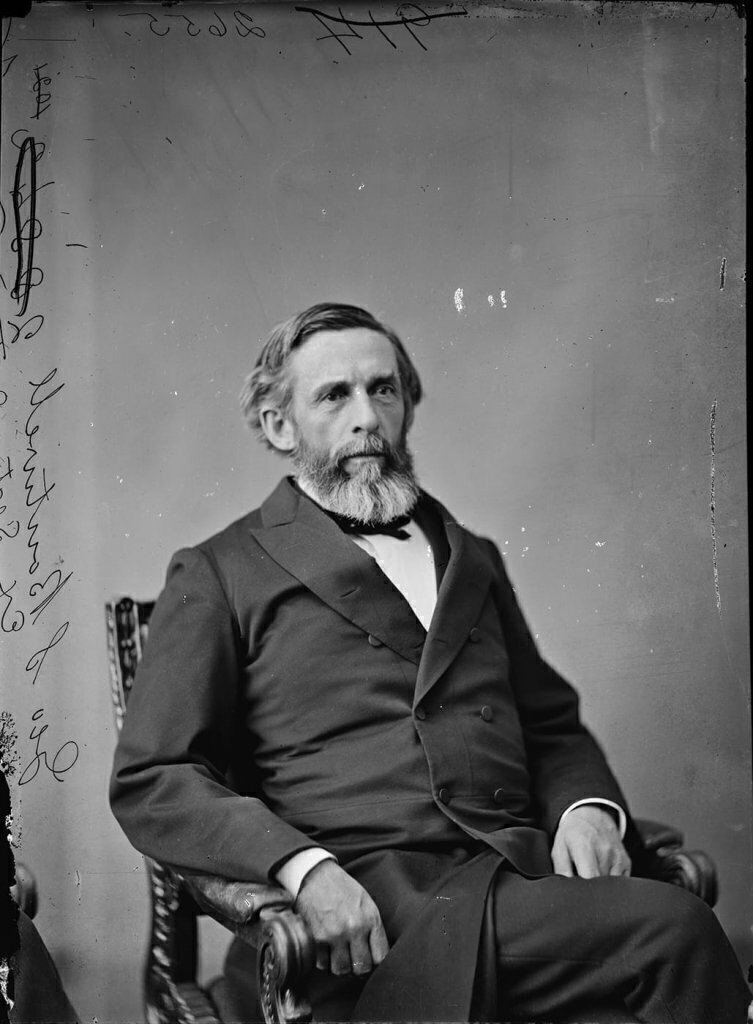

The Reconstruction Acts were an emergency war measure designed to serve only until states were readmitted. To make black men's enfranchisement permanent, Republicans began to debate another constitutional amendment. In January 1869, George Boutwell proposed a suffrage amendment in the House, and John Brooks Henderson introduced a similar amendment in the Senate.

January 11, 1869

This draft was similar to the final text. It focused squarely on race and did not explicitly protect office-holding. Rep. John Bingham believed this draft was too limited in scope. Recommended to the House Judiciary Committee. House passed (150-42).

January 11, 1869

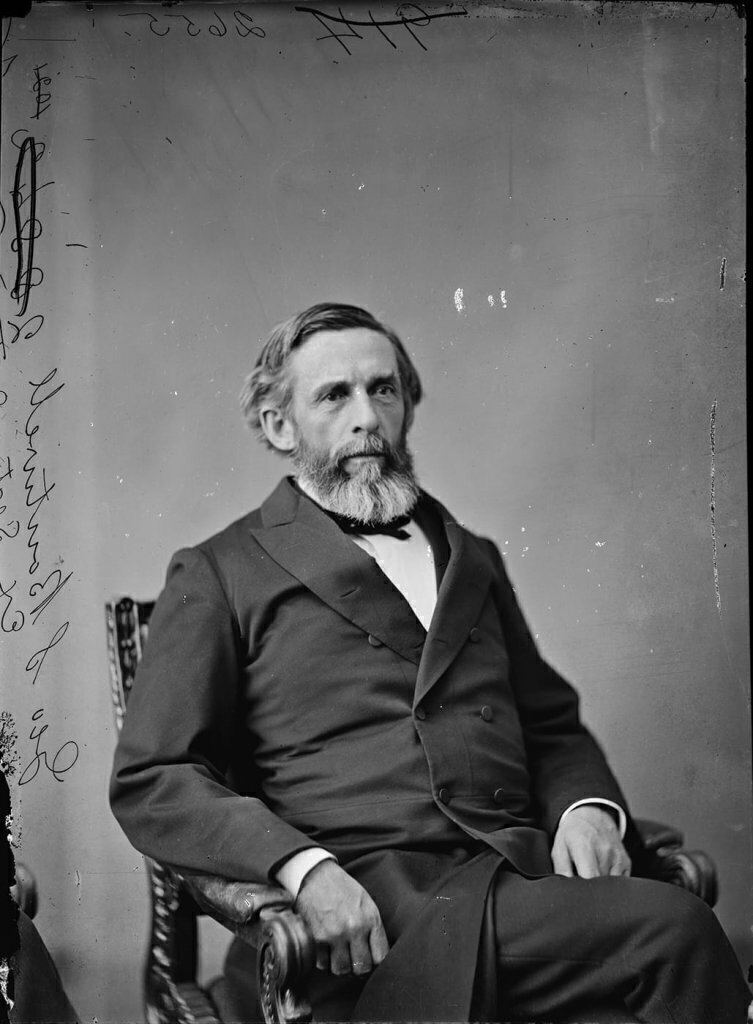

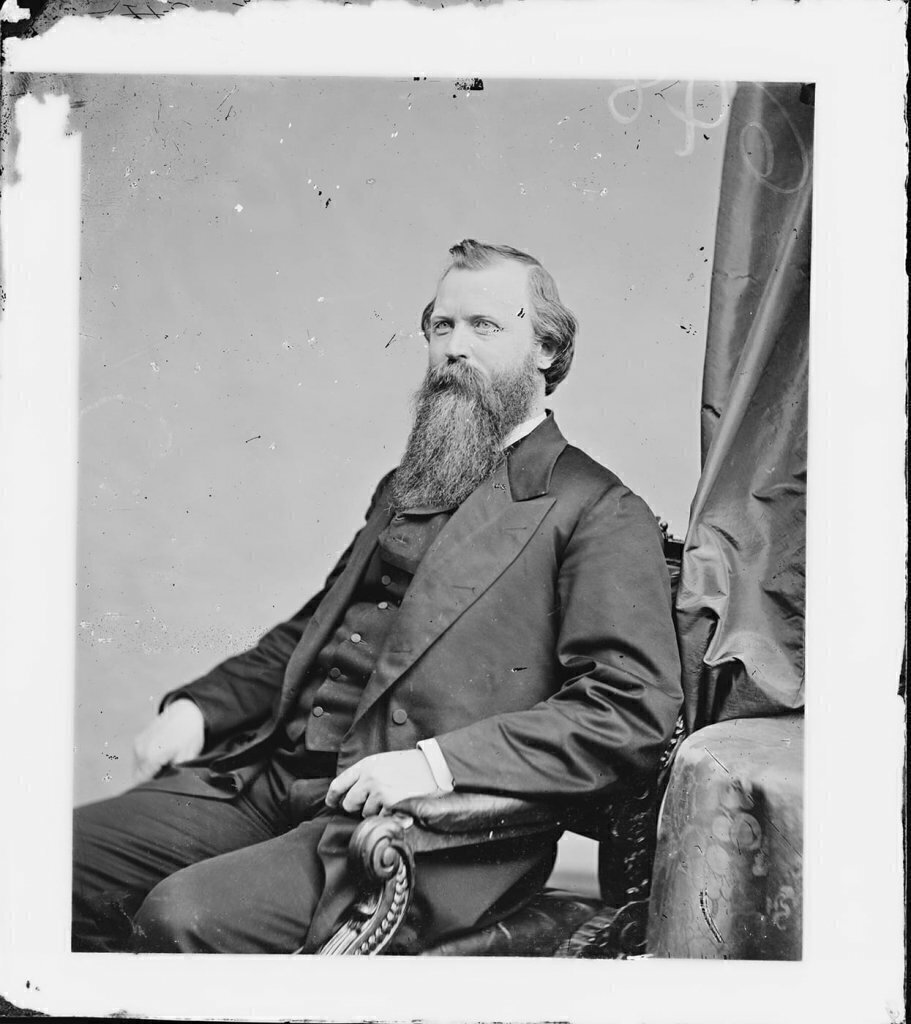

George Boutwell

U.S. Representative, Republican, Massachusetts

The right of any citizen of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of the race, color, or previous condition of slavery of any citizen or class of citizens of the United States. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This would be the first amendment to directly address voting. Like the final text, this draft focused squarely on racial discrimination, attacking both state and national abuses. Other drafts—including proposals that passed one house of Congress—swept more broadly. The Congress shall have power to enforce by proper legislation the provisions of this article. Previous amendments limited national power. The Reconstruction Amendments would be the first to empower the national government—a significant innovation that future amendments would follow.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 11, 1869

George Boutwell

U.S. Representative, Republican, Massachusetts

The right of any citizen of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of the race, color, or previous condition of slavery of any citizen or class of citizens of the United States. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This would be the first amendment to directly address voting. Like the final text, this draft focused squarely on racial discrimination, attacking both state and national abuses. Other drafts—including proposals that passed one house of Congress—swept more broadly. The Congress shall have power to enforce by proper legislation the provisions of this article. Previous amendments limited national power. The Reconstruction Amendments would be the first to empower the national government—a significant innovation that future amendments would follow.

Select a Document

January 23, 1869

This draft was limited to race, but it included protections for voting and office-holding. Senate Judiciary Committee and the Committee of the Whole considered. After debate, language tweaked and passed by committee.

January 23, 1869

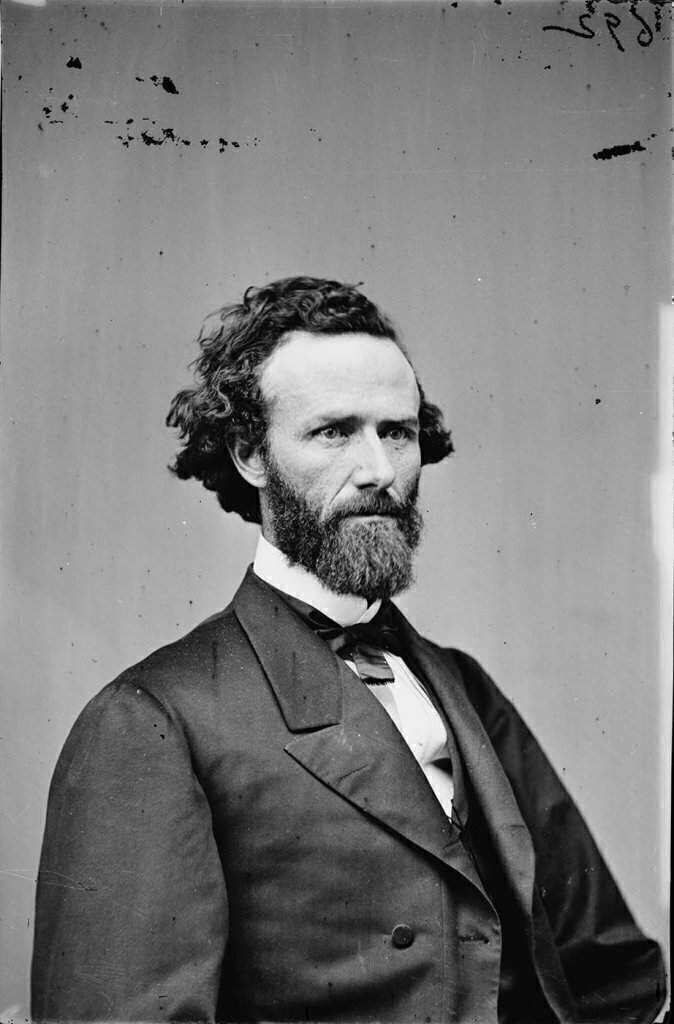

John Brooks Henderson

U.S. Senator, Republican, Missouri

No State shall deny or abridge the right of its citizens to vote and hold office on account of race, color, or previous condition. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This would be the first amendment to directly address voting—restricting state authority and carving out a role for the national government to protect against abuses. Congress debated whether to cover just voting or voting and office-holding, like it did here. The final text only explicitly protected voting. Like the final text, this language focuses squarely on race. Other drafts—including proposals that passed one of the houses of Congress—swept more broadly. The Congress by appropriate legislation, may enforce the provisions of this article. Previous amendments limited national power. The Reconstruction Amendments would be the first to empower the national government—a significant innovation that future amendments would follow.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 23, 1869

John Brooks Henderson

U.S. Senator, Republican, Missouri

No State shall deny or abridge the right of its citizens to vote and hold office on account of race, color, or previous condition. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This would be the first amendment to directly address voting—restricting state authority and carving out a role for the national government to protect against abuses. Congress debated whether to cover just voting or voting and office-holding, like it did here. The final text only explicitly protected voting. Like the final text, this language focuses squarely on race. Other drafts—including proposals that passed one of the houses of Congress—swept more broadly. The Congress by appropriate legislation, may enforce the provisions of this article. Previous amendments limited national power. The Reconstruction Amendments would be the first to empower the national government—a significant innovation that future amendments would follow.

Select a Document

January 27, 1869

This broad proposal was not limited to race. It guaranteed that all men over 21 who were of “sound mind”—and with few other exceptions—could vote. House rejected (24-160).

January 27, 1869

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge or deny to any male citizen of the United States, of sound mind, and over twenty-one years of age, the equal exercise of the elective franchise at all elections in the State wherein he shall have actually resided for a period of one year next preceding such election, except such of said citizens as shall hereafter engage in rebellion or insurrection, or who may have been or shall be duly convicted of treason or other crime of the grade of felony at common law. Broader than other proposals, this provision was not limited to racial discrimination. It guaranteed all male citizens over 21 and of “sound mind” the right to vote—subject to few other restrictions. While providing broad protections for voting, this draft did explicitly allow states to exclude felons and those who engaged in future rebellions from voting. It did not touch the ex-Confederates.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 27, 1869

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge or deny to any male citizen of the United States, of sound mind, and over twenty-one years of age, the equal exercise of the elective franchise at all elections in the State wherein he shall have actually resided for a period of one year next preceding such election, except such of said citizens as shall hereafter engage in rebellion or insurrection, or who may have been or shall be duly convicted of treason or other crime of the grade of felony at common law. Broader than other proposals, this provision was not limited to racial discrimination. It guaranteed all male citizens over 21 and of “sound mind” the right to vote—subject to few other restrictions. While providing broad protections for voting, this draft did explicitly allow states to exclude felons and those who engaged in future rebellions from voting. It did not touch the ex-Confederates.

Select a Document

January 28, 1869

This draft focused on race and extended protections to voting and office-holding. Some senators objected to the limited scope. Changed slightly and passed the Senate (35-11) before being rejected by the House.

January 28, 1869

Senate Judiciary Committee

40th Congress

The right of citizens of the United States to vote, and hold office shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This proposal would directly address voting. Congress debated whether to cover just voting or voting and office-holding, as in this draft. The final text only explicitly protected voting. Like the final text, this language focused squarely on racial discrimination, limiting both state and national authority. Other drafts—including proposals that passed one of the houses of Congress—swept more broadly.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 28, 1869

Senate Judiciary Committee

40th Congress

The right of citizens of the United States to vote, and hold office shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This proposal would directly address voting. Congress debated whether to cover just voting or voting and office-holding, as in this draft. The final text only explicitly protected voting. Like the final text, this language focused squarely on racial discrimination, limiting both state and national authority. Other drafts—including proposals that passed one of the houses of Congress—swept more broadly.

Select a Document

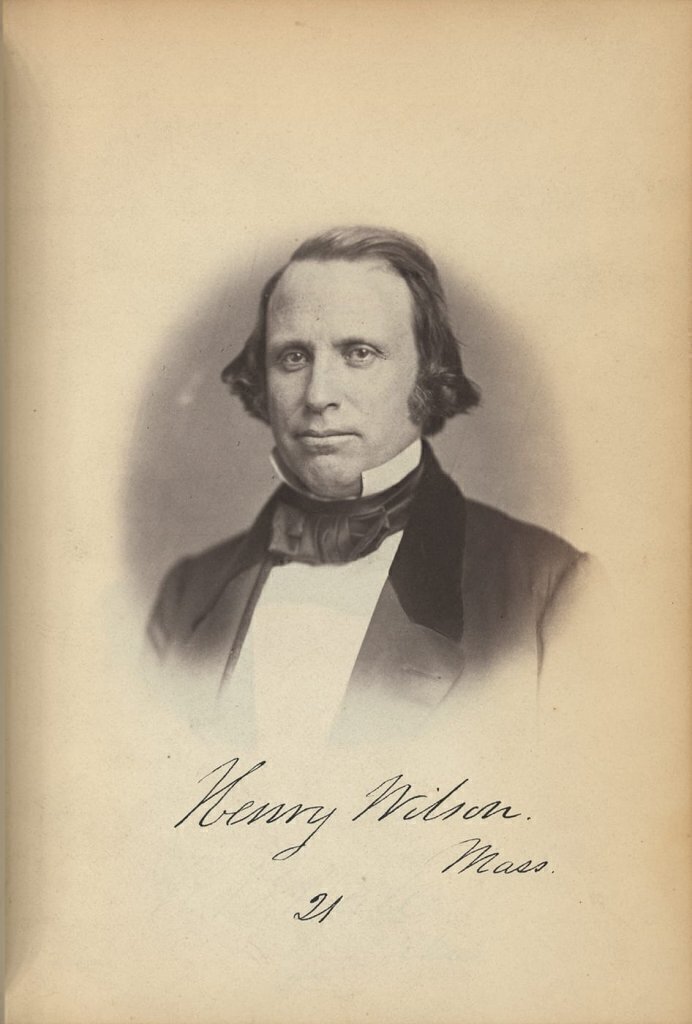

February 8, 1869

This draft protected voting and office-holding. It also protected against multiple forms of discrimination—not just racial discrimination. Bingham agreed with this proposal because it identified more forms of discrimination, not just race. Senate passed, but it failed in the House (37 to 133). Later rescinded by the Senate.

February 8, 1869

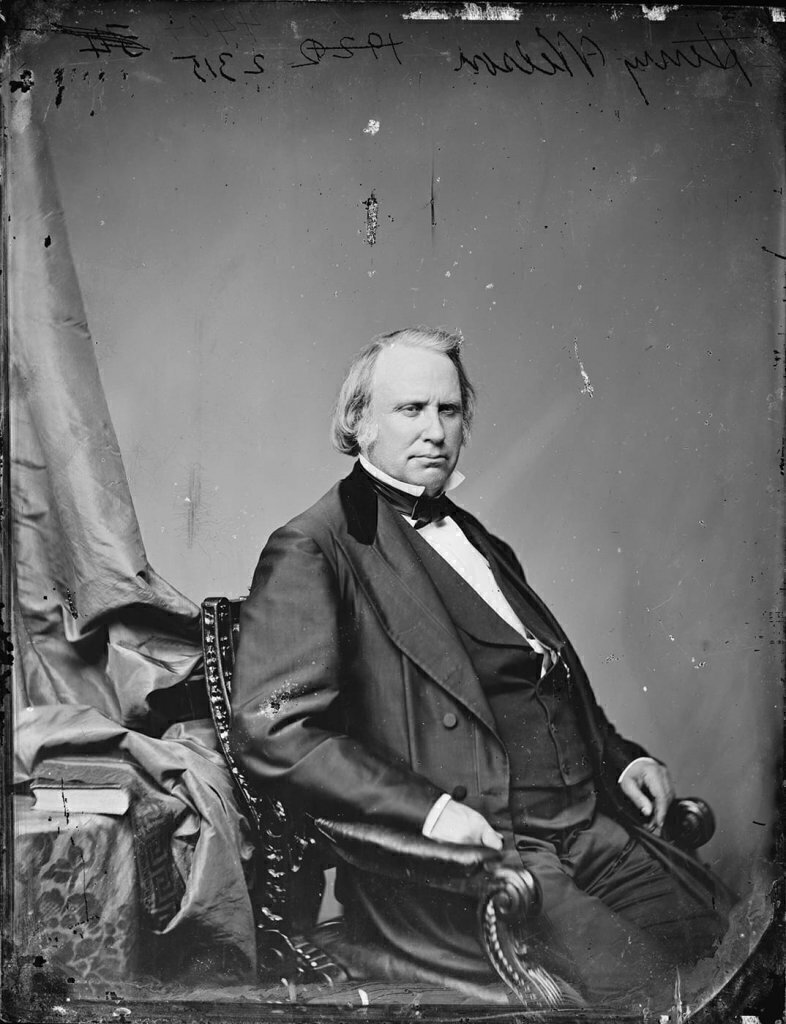

Henry Wilson

U.S. Senator, Republican, Massachusetts

No discrimination shall be made in any State among the citizens of the United States in the exercise of the elective franchise or in the right to hold office in any State on account of race, color, nativity, property, education, or creed. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This amendment sought to restrict the states' ability to discriminate in voting. Congress debated whether to cover just voting or voting and office-holding, as in this draft. The final text only explicitly protected voting.This provision swept more broadly than the final text. It focused not only on race, but also on “nativity, property, education, or creed”—language that might have been used to attack future Jim Crow laws like poll taxes and literacy tests.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.February 8, 1869

Henry Wilson

U.S. Senator, Republican, Massachusetts

No discrimination shall be made in any State among the citizens of the United States in the exercise of the elective franchise or in the right to hold office in any State on account of race, color, nativity, property, education, or creed. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This amendment sought to restrict the states' ability to discriminate in voting. Congress debated whether to cover just voting or voting and office-holding, as in this draft. The final text only explicitly protected voting.This provision swept more broadly than the final text. It focused not only on race, but also on “nativity, property, education, or creed”—language that might have been used to attack future Jim Crow laws like poll taxes and literacy tests.

Select a Document

February 20, 1869

This draft protected voting and office-holding. It also provided protections against multiple forms of discrimination—not just racial discrimination. House passed (92-70), but Senate refused and called for a conference committee of both houses.

February 20, 1869

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

The right of citizens of the United States to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged by any State on account of race, color, nativity, property, creed, or previous condition of servitude. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This would directly address voting. Congress debated whether to cover just voting or voting and office-holding, as in this draft. The final text only explicitly protected voting. This provision swept more broadly than the final text. It focused not only on race, but also on “nativity, property,” and “creed”—language that might have been used to attack future Jim Crow laws like poll taxes.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.February 20, 1869

John Bingham

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

The right of citizens of the United States to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged by any State on account of race, color, nativity, property, creed, or previous condition of servitude. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This would directly address voting. Congress debated whether to cover just voting or voting and office-holding, as in this draft. The final text only explicitly protected voting. This provision swept more broadly than the final text. It focused not only on race, but also on “nativity, property,” and “creed”—language that might have been used to attack future Jim Crow laws like poll taxes.

Select a Document

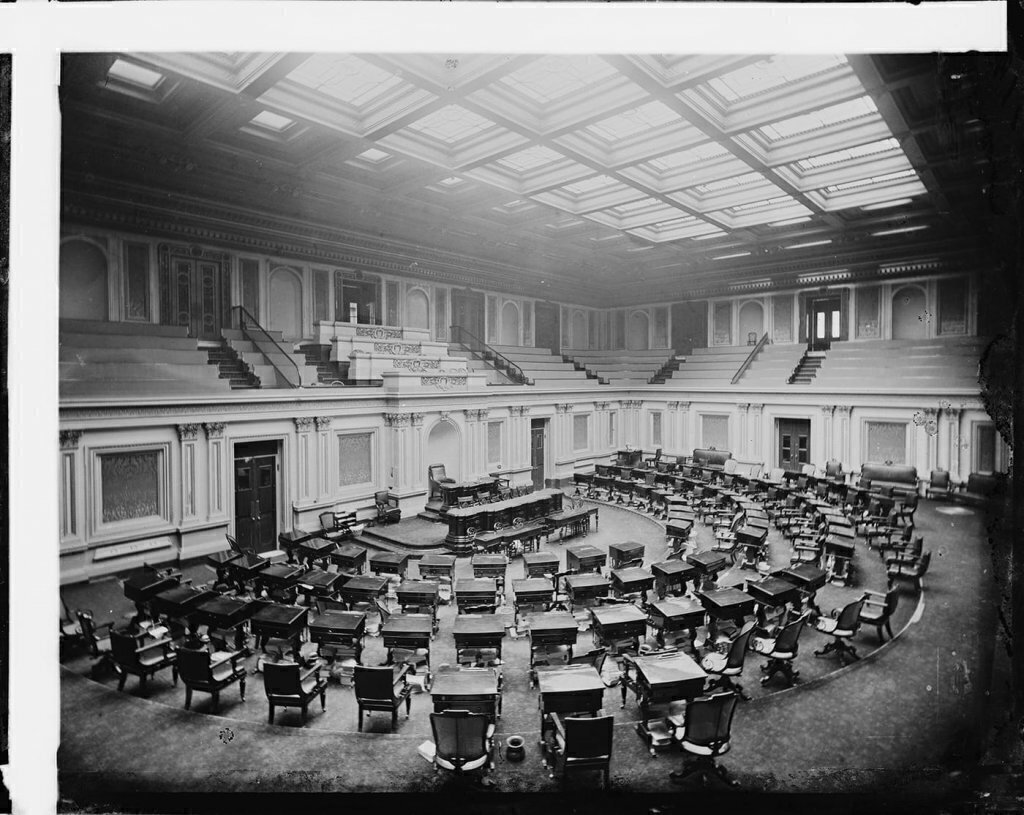

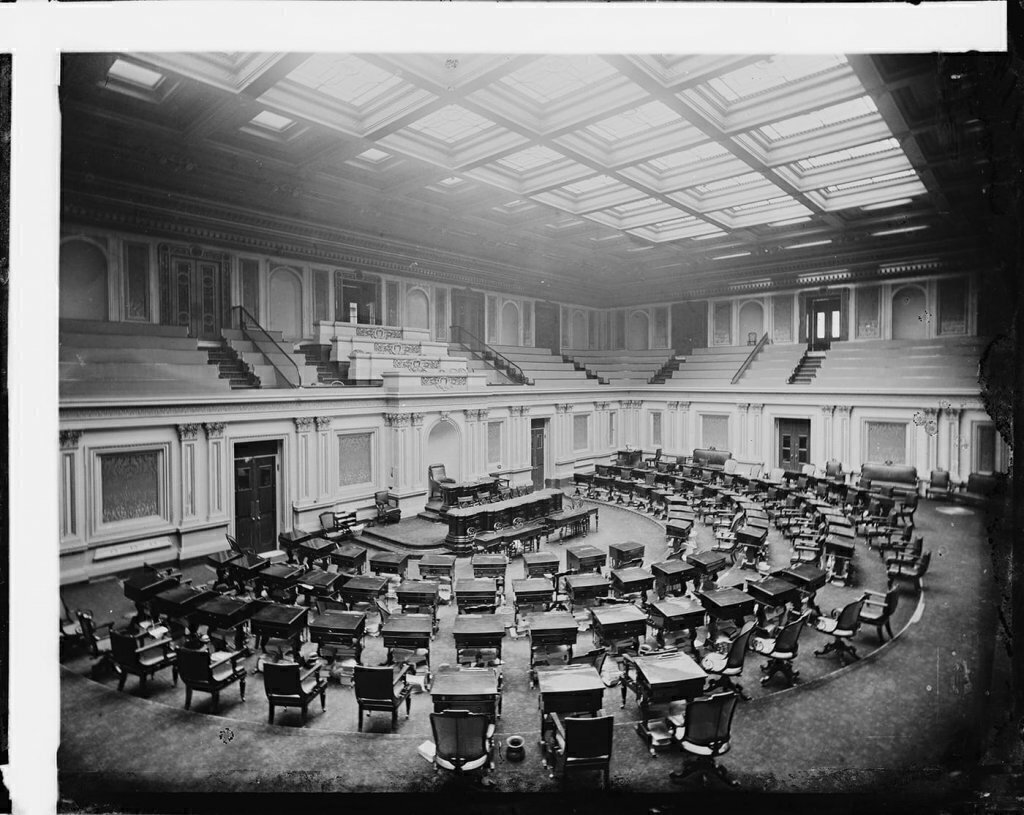

February 23, 1869

With the House and Senate unable to settle on a common proposal, the Senate called for a Conference Committee between both chambers of Congress. The committee finalized the language and reported out a proposed amendment two days later.

February 25, 1869

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

February 25, 1869

Congressional Conference Committee

40th Congress

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This would be the first amendment to directly address voting. This language also focused squarely on race, protecting citizens from discrimination by the national government or the states. Other drafts—including proposals that passed one of the houses of Congress—swept more broadly.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.February 25, 1869

Congressional Conference Committee

40th Congress

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. The Constitution originally left who could vote in elections to the states. This would be the first amendment to directly address voting. This language also focused squarely on race, protecting citizens from discrimination by the national government or the states. Other drafts—including proposals that passed one of the houses of Congress—swept more broadly.

Select a Document

February 26, 1869

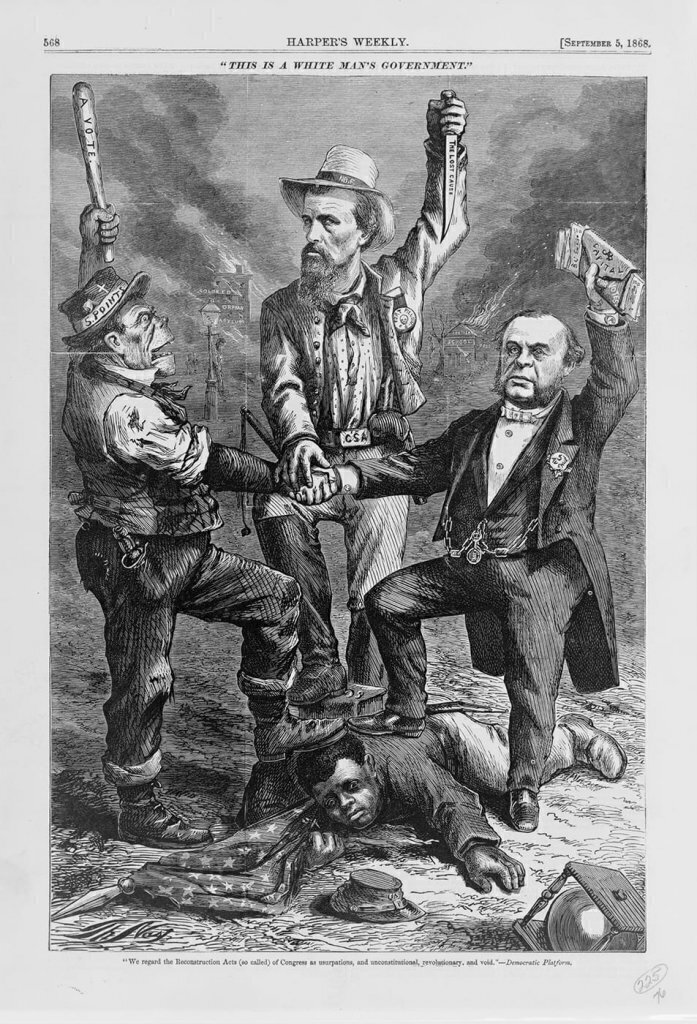

The 15th Amendment transformed the Constitution—banning racial discrimination in voting. The final text was narrower than earlier proposals, focusing squarely on race and excluding protections for office-holding. In February 1869, the House passed it (144-44), followed by the Senate (39-13). As Frederick Douglass declared, “The revolution wrought in our condition by the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution of United States, is almost startling, even to me. I view it with something like amazement.”

February 26, 1869

40th Congress

Final Amendment

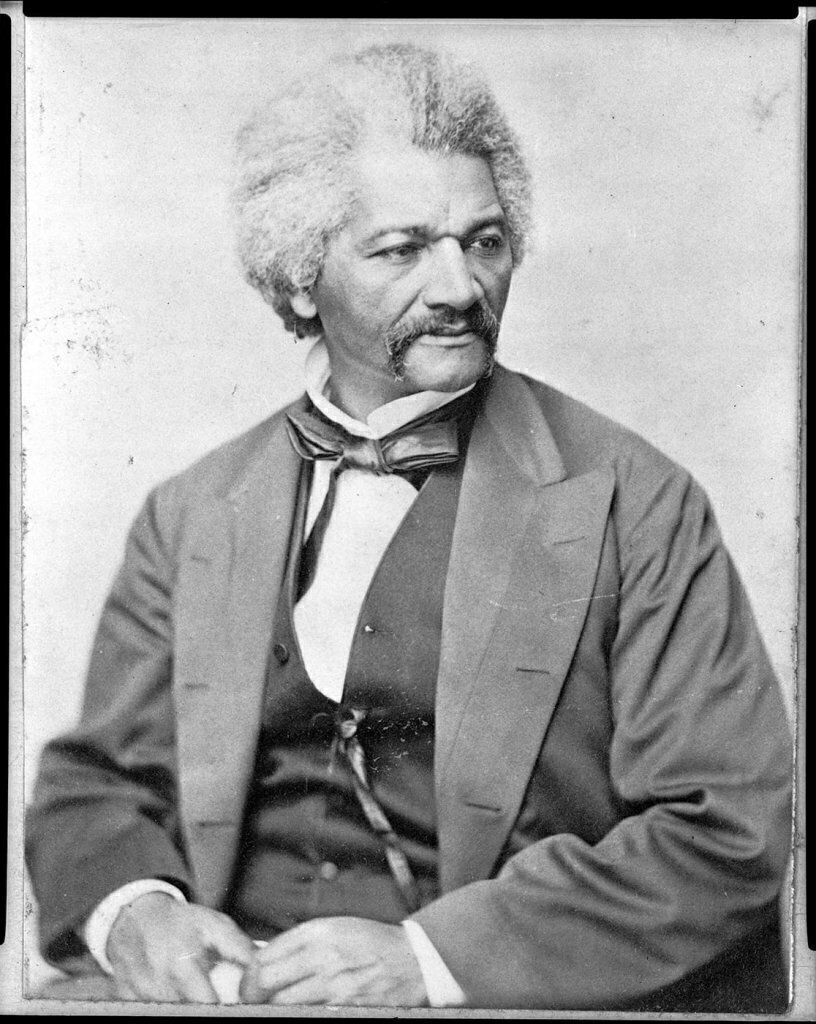

Section One The right of citizens of the United States to vote This provision was the first to directly address voting rights. The Constitution originally let states determine who could vote in elections, and African Americans had long called for access to the ballot. By defending the Union cause on the battlefield and risking their lives to flee enemy lines, black men laid claim to this new protection. shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. The final text focused on voting and race. Earlier drafts—including proposals that passed one congressional house—swept more broadly. Republicans disagreed over whether the amendment should cover office-holding. They also debated whether to cover other forms of voter discrimination. None of these additional protections made it into the final text. Section Two The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. This section follows the other Reconstruction Amendments in granting Congress the power to enforce its provisions. While the original Constitution left the issue of voting to the states, this section enabled Congress to protect African Americans from racial discrimination in voting. Congress eventually used this power to pass the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.February 26, 1869

40th Congress

Final Amendment

Section One The right of citizens of the United States to vote This provision was the first to directly address voting rights. The Constitution originally let states determine who could vote in elections, and African Americans had long called for access to the ballot. By defending the Union cause on the battlefield and risking their lives to flee enemy lines, black men laid claim to this new protection. shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. The final text focused on voting and race. Earlier drafts—including proposals that passed one congressional house—swept more broadly. Republicans disagreed over whether the amendment should cover office-holding. They also debated whether to cover other forms of voter discrimination. None of these additional protections made it into the final text. Section Two The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. This section follows the other Reconstruction Amendments in granting Congress the power to enforce its provisions. While the original Constitution left the issue of voting to the states, this section enabled Congress to protect African Americans from racial discrimination in voting. Congress eventually used this power to pass the 1965 Voting Rights Act.